DACA: Rescinding DACA, Revictimizing Victims

By: Raio Krishnayya, CVHR Executive Director and Jessica Topor, CVHR Supervisory Staff Attorney

Ana came to the United States with her family in 1997 when she was 4 years old. Her family travelled almost 3,000 miles, mostly on foot, to escape violence in their home country of El Salvador and provide a measure of safety for Ana and her siblings. The United States is the only country Ana knows, and one she is proud to call home.

One of the only remedies available for an individual like Ana to legally work in the United States and live without constant fear of deportation is through Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). However, on September 5, President Trump announced that he would rescind DACA, which, per the Pew Research Center, will affect nearly 790,000 otherwise unauthorized immigrants.

Proponents of the Trump Administration policy justify the decision under the rhetoric, ‘they’re here illegally.’ Unfortunately, this oversimplification fails to acknowledge that not every person in that class of 790,000 is the same. Most, like Ana, had no real choice in determining where she grew up.

After becoming a DACA recipient, Ana graduated at the top of her class and started a career. She entered a relationship and had a child. After her daughter’s birth, however, Ana’s relationship turned violent, with Ana and her daughter becoming victims of domestic violence. She called the police, knowing that threats of deportation by the abuser, were baseless due to her DACA status. Rescinding DACA, however, removes that safe harbor. Rescinding DACA gave the abuser’s threats ‘teeth.’

Domestic violence is about power and control and although often manifests in physical violence, for immigrant victims, the power and control manifests through an abuser’s threats of deportation of the victim. These threats can be as brutal as the physical abuse, and the fear is amplified for undocumented victims, telling them, “You will be ripped from your home, taken in the middle of the night by men with weapons, thrown in a hole, and taken away from your children. You will be forgotten, and no one will care.”

For us, as attorneys who help victims like Ana, the most daunting hurdle is simply fostering trust that we are not trying to deport our clients, we don’t work for the government, we want to stop the abuse, and that law enforcement and prosecutors are concerned about stopping domestic violence. However, the end of DACA takes away another bridge for us to make that connection and build trust, and ends up empowering an already empowered abuser.

Without DACA, a person who was brought to the United States as a child and victimized by a family or household member may not feel safe calling 911 because of the false choice: call and get help or be deported and torn from your family, your home. Without DACA, domestic violence victims with no other options will be repeatedly victimized.

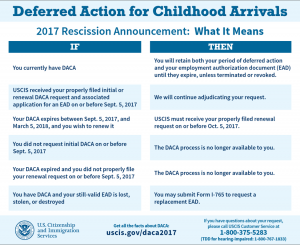

Concerned about your status as an unauthorized immigrant or DACA recipient? Read the following chart for guidance on what your next steps should be:

For more information on Center for Victim and Human Rights (CVHR), visit their website!