Community Wide Plan: A Recap and Look Forward

Written by Mary-Margaret Sweeney, Director of Community Engagement

As 2017 wraps up, we close out the second section of our Community Wide Plan, Intersections. Our framework is to spend 6 months on each of the 6 identified social issue that intersects with domestic violence. For 2017, we focused on domestic violence and economics January-June, and ended the year working on domestic violence and childhood experiences, July-December.

I will be upfront with you, Network, in saying that I feel the last six months did not get it’s due. I took over the role of Director of Community Engagement in June, and spent the last six months juggling both my former position as Training Services Manager and the new role. In that time I wove childhood experiences into my standard trainings around domestic violence but close this year wishing I had done more. Yet I know that just because we are moving on to two new topics in 2018, that childhood experiences will be, and in fact have to be, an ongoing part of the way we endeavor to eliminate domestic violence in our city. What we witness and experience as children impacts us for the rest of our days. It affects the education we receive–our next plan topic. It impacts our mental health into adulthood–the topic of the second half of 2018. My training as a social worker, my perpetual study of new evidence-based interventions and best practices, and my conversations with the community let me know this is true. And, anecdotally, my own childhood trauma–and protective factors–remind me this is paramount to any discussion we have.

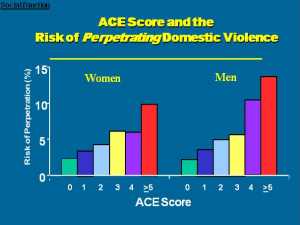

My father grew up in a violent home. They had all the risk factors for domestic violence and boy, did those risks deliver. At 13 my father stood between his mother and father to protect her, was struck by his father, and told him to leave the home. They never saw him again. I know now that research says my father was at a significant risk of becoming a perpetrator of violence in my childhood home (see graph below). Instead, he eschewed all violence, adopting a pacifist belief system. But his trauma was evident: typical loud childhood noise-making on my part made him extremely nervous, especially at the dinner table. In his home, dinner quickly devolved into thrown food, screams, and bruises. I never got a pass from him when I was unkind to another child. To him, any unkindness was violence.

My father had many health problems from a young age (many of them we now know are extremely prevalent in those with high rates of childhood trauma). He died when I was in kindergarten. For years afterward, I was chronically absent from school. I had severe stomach aches and insomnia that actually made me physically ill; but I too had days where I would fake these symptoms in order to stay home. Not because I didn’t like school, because I loved learning and reading and seeing my friends. But, I was afraid to lose my mother too, and wanted to be with her at all times. I didn’t have the words to verbalize that at 6, or even 10. I just knew that many times when my mother was about to leave me somewhere, that I would start breathing differently, would start imagining her in a car accident or some other tragic situation, and my mind would reel with thoughts about where I would live, who would care for me, and what would happen to our dog. This would often strike in the middle of my school day and the rest of the afternoon my brain would fixate on these terrible daydreams, only aware of the clock in the classroom, counting down the minutes until I could make sure she was alright and I would not be an orphan. My education was impacted by these absences and daydreams.

But preventing children from experiencing trauma first hand is not enough. Fascinating research is emerging regarding generational trauma, in the field of epigenetics. We are learning that children and grandchildren of someone who has experienced trauma is impacted, even if they did not experience the trauma themselves. Trauma changes us on a cellular level, and those that come after us. When we know that so many of our youth are experiencing the trauma of witnessing domestic violence at home (anywhere between 5 and 15 million, depending on what study you read), we can predict that over time and generations, we have a significant problem on our hands. When we factor in other traumas of childhood–losing a parent to death, like me; the experience of emigrating; witnessing community violence; child abuse–the cost to our community, for decades to come, cannot be overstated.

As we move into 2018 and engage the community to address the intersection of domestic violence and education, I promise you that DVN will keep this reality at the forefront. I hope you join us next year in this critical work.